Hacking Vulnerable Bank API - Part 1

Dec. 9, 2025

In 2019, First American Financial Corporation leaked 885 million sensitive financial records. The cause was not a sophisticated malware attack or a compromised firewall; it was a logic vulnerability known as Insecure Direct Object Reference (IDOR), now classified under Broken Object Level Authorization (BOLA). By simply changing a number in a URL, unauthorized individuals could access mortgage documents belonging to other customers.

This incident underscores a critical reality in the financial sector: application logic is often the weakest link.

This past week, I spent time testing the Vulnerable Bank API as part of my API Security training with CyberSafe Foundation. My goal was to move past the theory and find and exploit vulnerabilities in a real application.

In this article, I’ll walk through how I found some security flaws in how the application handles logins, permissions, and sensitive data. I’ll also explain how these same issues show up in real-world financial systems.

Environment and Methodology

To simulate a realistic threat scenario, I set up a hybrid testing environment. My goal was to attack the application from an isolated machine (Kali Linux) just as an external attacker or malicious insider might.

Setting up the Target

For the target application, I used the Vulnerable Bank API, a deliberately insecure banking application created by Commando-X. You can find the project and installation instructions on GitHub here: Commando-X/vuln-bank.

Since I already had Docker installed on my Windows host machine, deploying the application was straightforward. I simply followed the repository's instructions to pull the container and get it running locally. Once the container was up, the bank's API was accessible on my local network.

The Attack

I conducted all my testing from a Kali Linux Virtual Machine. This separation allowed me to use Kali's specialized security tools without cluttering my main Windows host. To make this work, I had to bridge the network so my Kali VM could "see" the Docker container running on Windows.

The Tools

To analyze and exploit the API, I needed two essential tools working in tandem: Postman and Burp Suite.

- Postman: I used Postman to organize and send API requests. After cloning the GitHub repository, I found the API documentation (often a Swagger/OpenAPI file) and imported it directly into Postman. This gave me a ready-to-use collection of every endpoint the bank offered, a map of the entire application.

- Burp Suite (The Interceptor): While Postman is great for sending requests, Burp Suite was used for intercepting and manipulating them. I configured Burp Suite as a proxy between Postman and the Vulnerable Bank. This allowed me to pause requests, modify data (like changing account IDs or injecting payloads), and see how the server responded.

With this pipeline established, i.e., Postman sending requests, Burp capturing them, and Vulnerable Bank processing them, I was ready to start the assessment.

1. Broken Object Level Authorization (BOLA)

BOLA is consistently ranked as the most severe API vulnerability for a reason: it exploits a fundamental failure in how servers validate ownership. It occurs when an application authorizes a user to access a specific resource (like a bank account) based solely on the user knowing the resource's ID, rather than verifying if the user owns it.

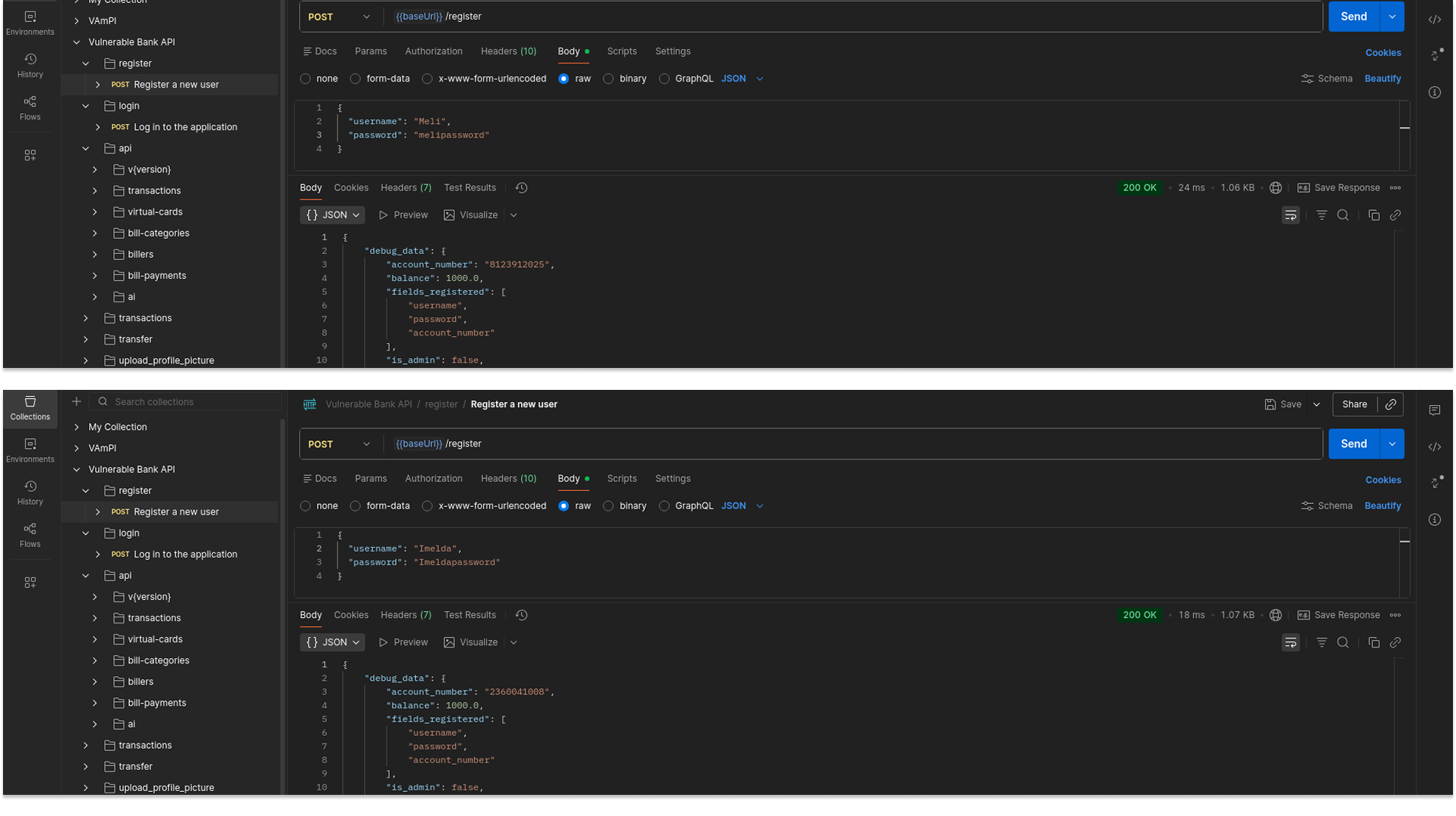

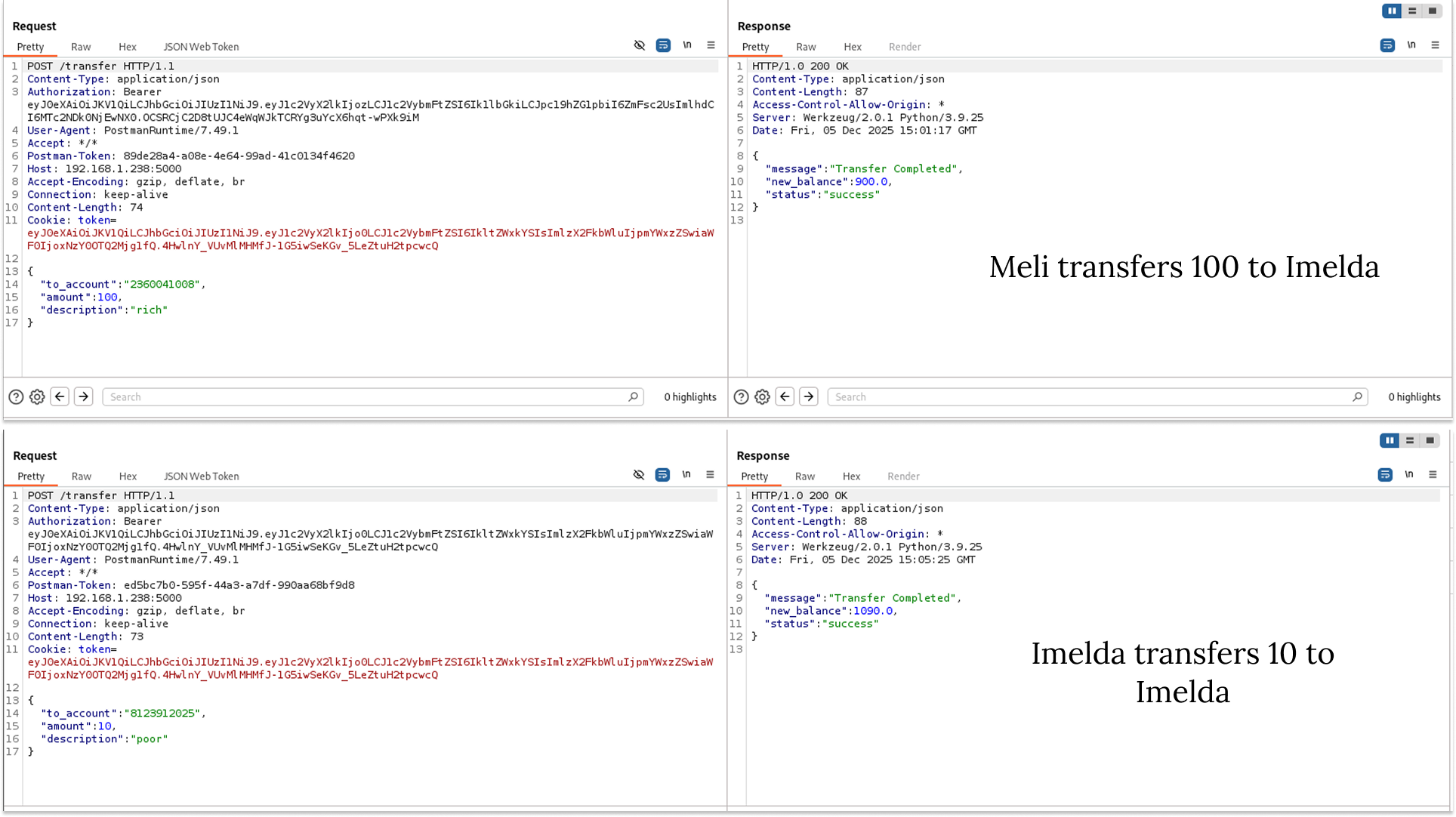

To demonstrate this vulnerability in a realistic setting, I needed more than just empty accounts. I started by registering two distinct users: "Meli" (the victim) and "Imelda" (the attacker). To populate the database with sensitive data, I simulated legitimate peer-to-peer transfers between them. Imelda sent money to Meli, and Meli sent money back. This created a transaction history that would serve to demonstrate a successful exploit.

Establishing the Session

First, I authenticated as the attacker, "Imelda," using the /login endpoint. The API responded with a valid JWT Bearer Token. This token proved my identity to the server, allowing me to pass the initial authentication.

Identifying the Target

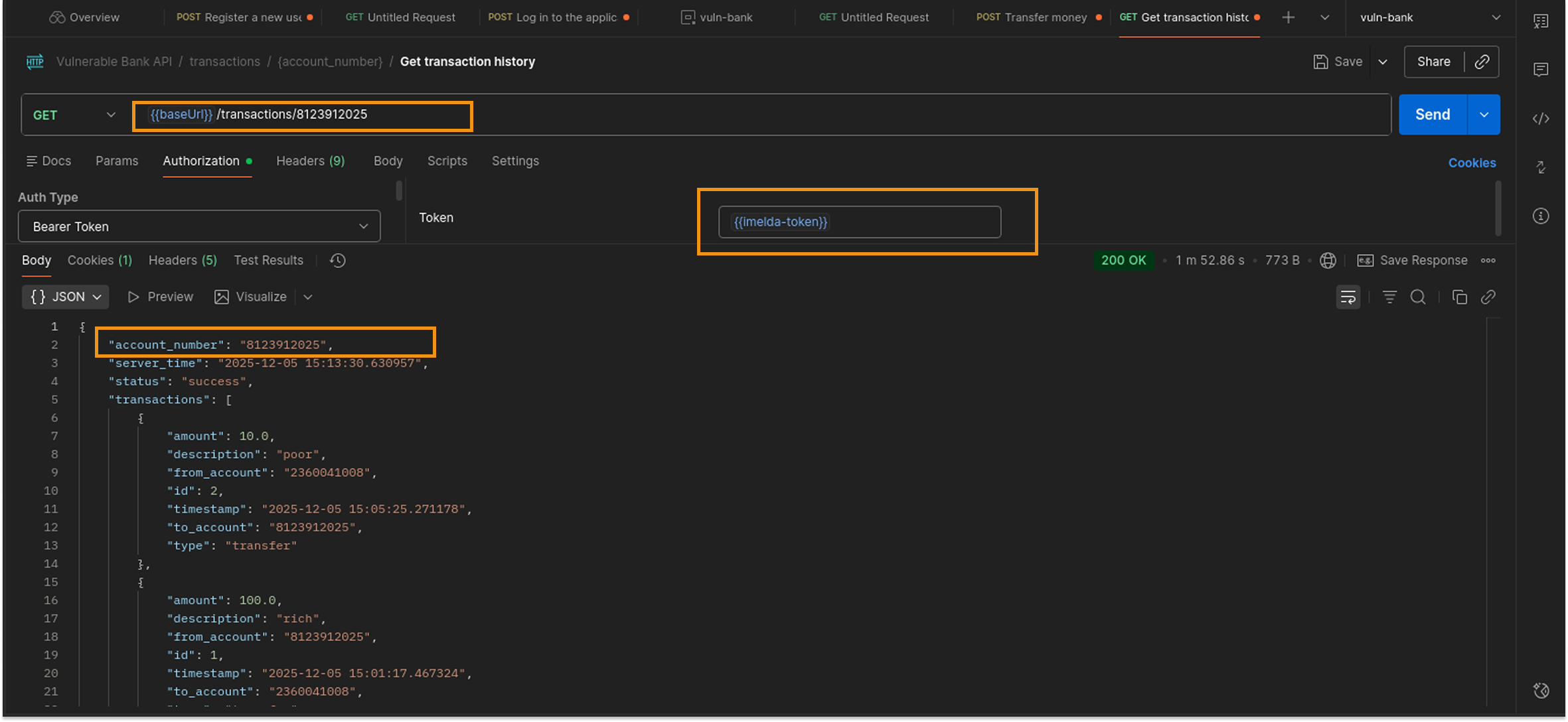

I identified the API endpoint responsible for retrieving transaction history: GET /transactions/{account_number}. In a normal workflow, the frontend application automatically fills in the {account_number} with the ID of the currently logged-in user. However, tools like Postman allow us to manipulate this value manually.

Executing the Attack

I set up a request in Postman with the following configuration:

- Header: I attached Imelda's (the attacker's) Bearer Token.

- URL: Instead of requesting Imelda's account number, I inserted Meli's Account Number (which I obtained from our previous legitimate transfers) into the URL path.

The Result

I sent the request, expecting a 403 Forbidden response. Instead, the API returned a 200 OK status.

The JSON response body contained Meli's complete transaction ledger with every deposit, withdrawal, and transfer timestamp visible.

Why this happened

The application performed Authentication correctly; it verified that my token was valid and that "Imelda" was a real user. However, it completely skipped the Authorization check. The code did not verify if the user_id inside the token matched the owner_id of the account requested in the URL. It simply trusted that if I had a valid key to the building, I was allowed to open every mailbox.

In a banking context, this vulnerability would allow a malicious actor to access the financial history of any user on the platform by simply guessing account numbers.

2. Broken Authentication:

Authentication systems are often most fragile in their recovery flows. While the main login might be secure, "Forgot Password" features frequently suffer from logic errors. To test this, I targeted the password reset functionality of the Vulnerable Bank.

My initial reconnaissance showed the application was using version 3 (v3) of the API for password resets. However, many APIs maintain older, less secure versions for backward compatibility. I decided to test if an older version existed and if it was more vulnerable.

Downgrading the API Version

While authenticated as the attacker ("Imelda"), I intercepted the password reset request in Burp Suite. The original endpoint was /api/v3/reset-password. I manually modified the URL path to target /api/v1/forgot-password instead. This "API Versioning" attack often reveals endpoints that lack modern security patches.

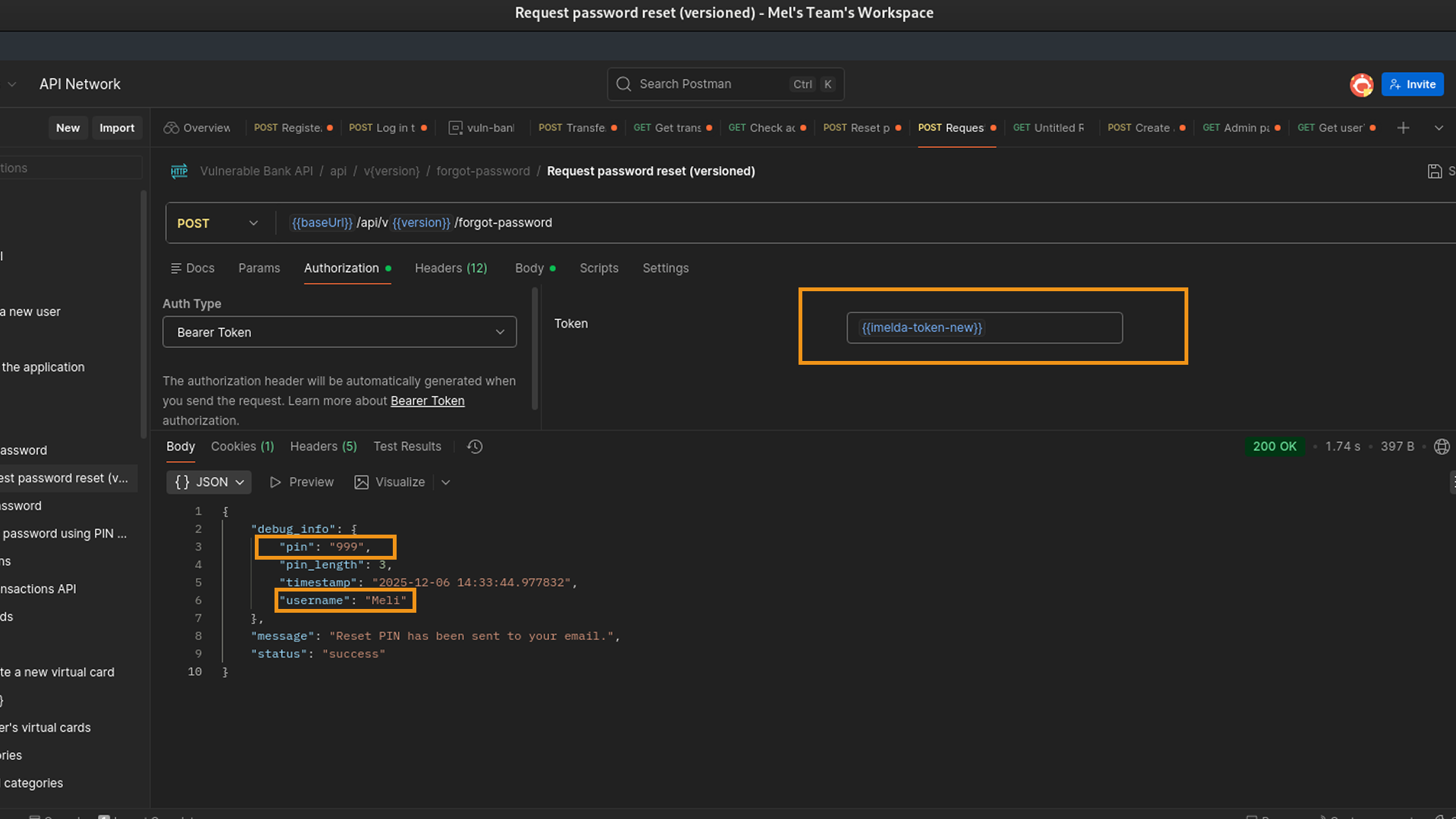

Triggering the Leak

I sent a POST request to this v1 endpoint, asking to reset the password for the victim, "Meli."

In a secure system, this should trigger an email to Meli. However, because I was hitting an older, likely debug-enabled version of the API, the server's response was catastrophic.

The JSON response body contained a debug_info object. Inside this object was the 3-digit PIN that the server intended to send to Meli's email.

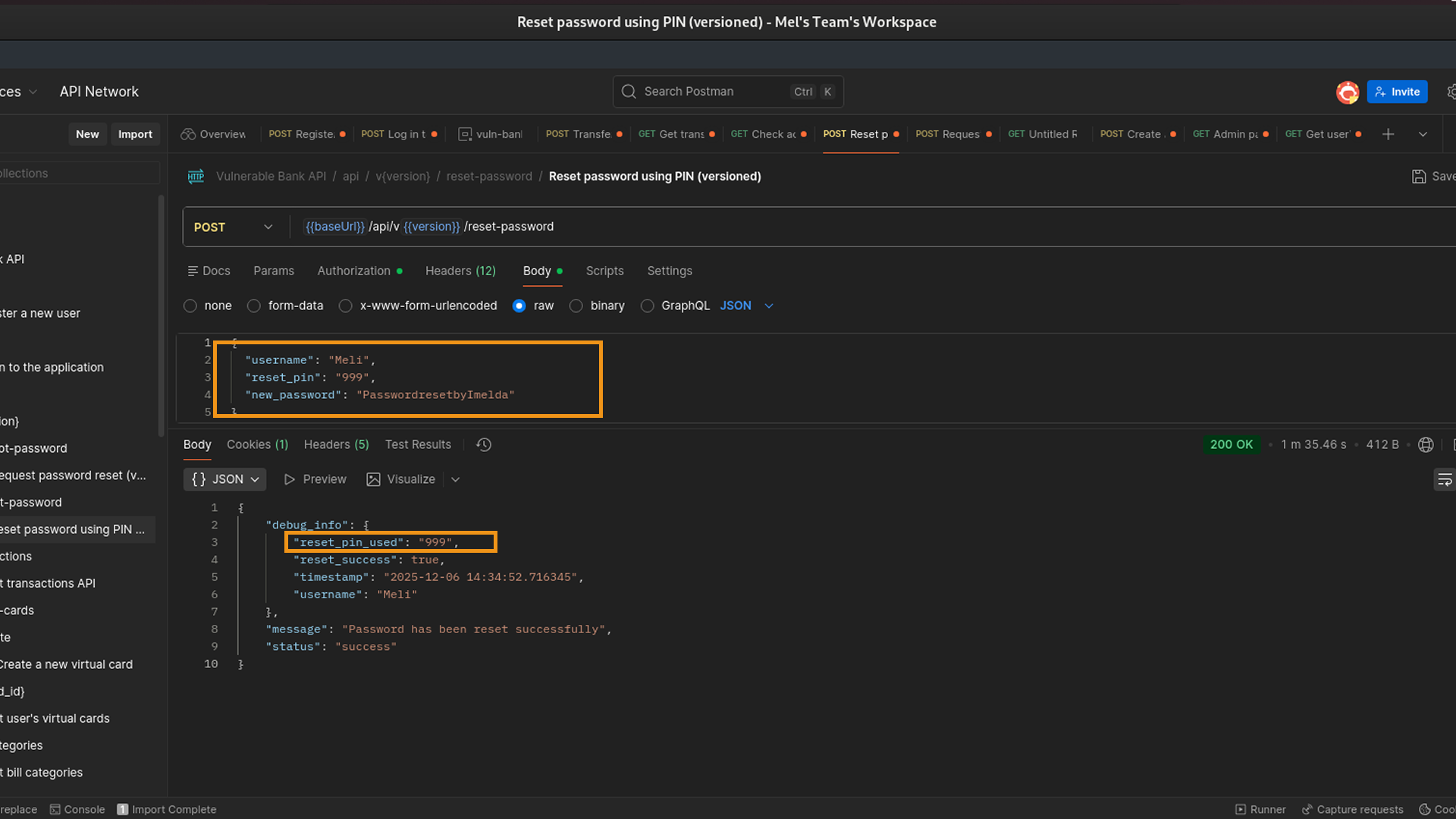

Completing the Takeover

With the secret PIN in hand, I no longer needed access to Meli's email. I went to the password reset confirmation endpoint (/api/v1/reset-password).

- Identity: I was still logged in as the attacker, "Imelda."

- Action: I submitted the stolen PIN along with a new password for Meli's account.

The Result

The API accepted the PIN and updated Meli's password. I was then able to log out of my attacker account and log straight into Meli's account using the new credentials I had just set.

This vulnerability mirrors critical issues seen in production environments where debug modes are left enabled or where legacy API versions are not properly decommissioned, allowing attackers to bypass robust current-day security controls.

3. Mass Assignment (Broken Object Property Level Authorization)

Mass Assignment occurs when an API blindly takes the data you send it and dumps it directly into the database without checking if you are allowed to modify those specific fields. It is like filling out a job application and adding a line at the bottom that says "Starting Salary: $1,000,000," and HR just accepts it because it was on the paper.

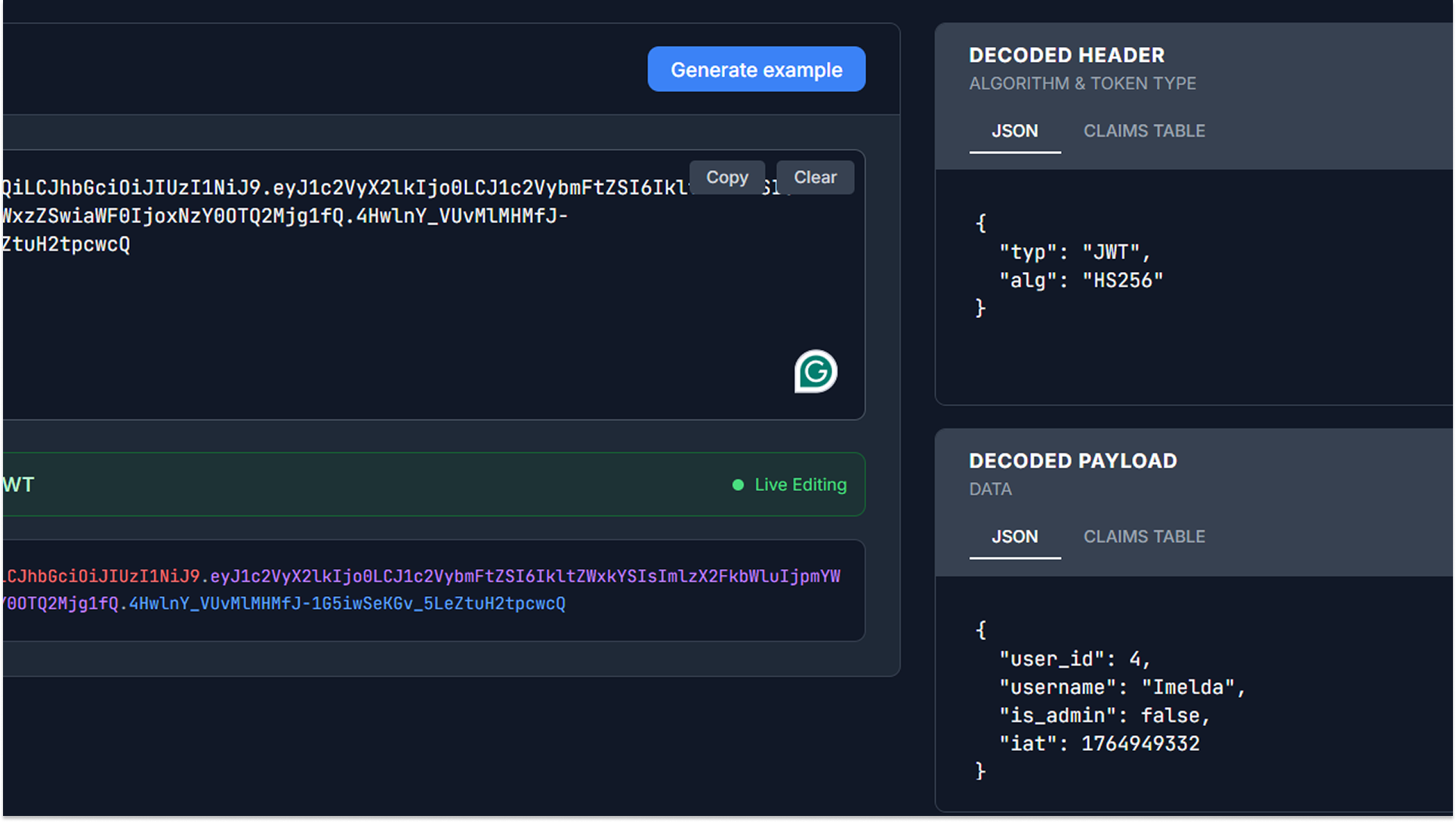

My investigation started not with the registration endpoint itself, but with the authentication token. I captured a standard user token and analyzed its structure on xjwt.io. Based on my previous research into The Anatomy of a JWT, I knew what to look for. The payload contained specific claims like "is_admin": false.

Seeing this field in the token gave me a hypothesis: If the application stores these values in the user object, and the registration endpoint creates that object, what happens if I just tell the API what I want those values to be during sign-up?

The Exploitation Path

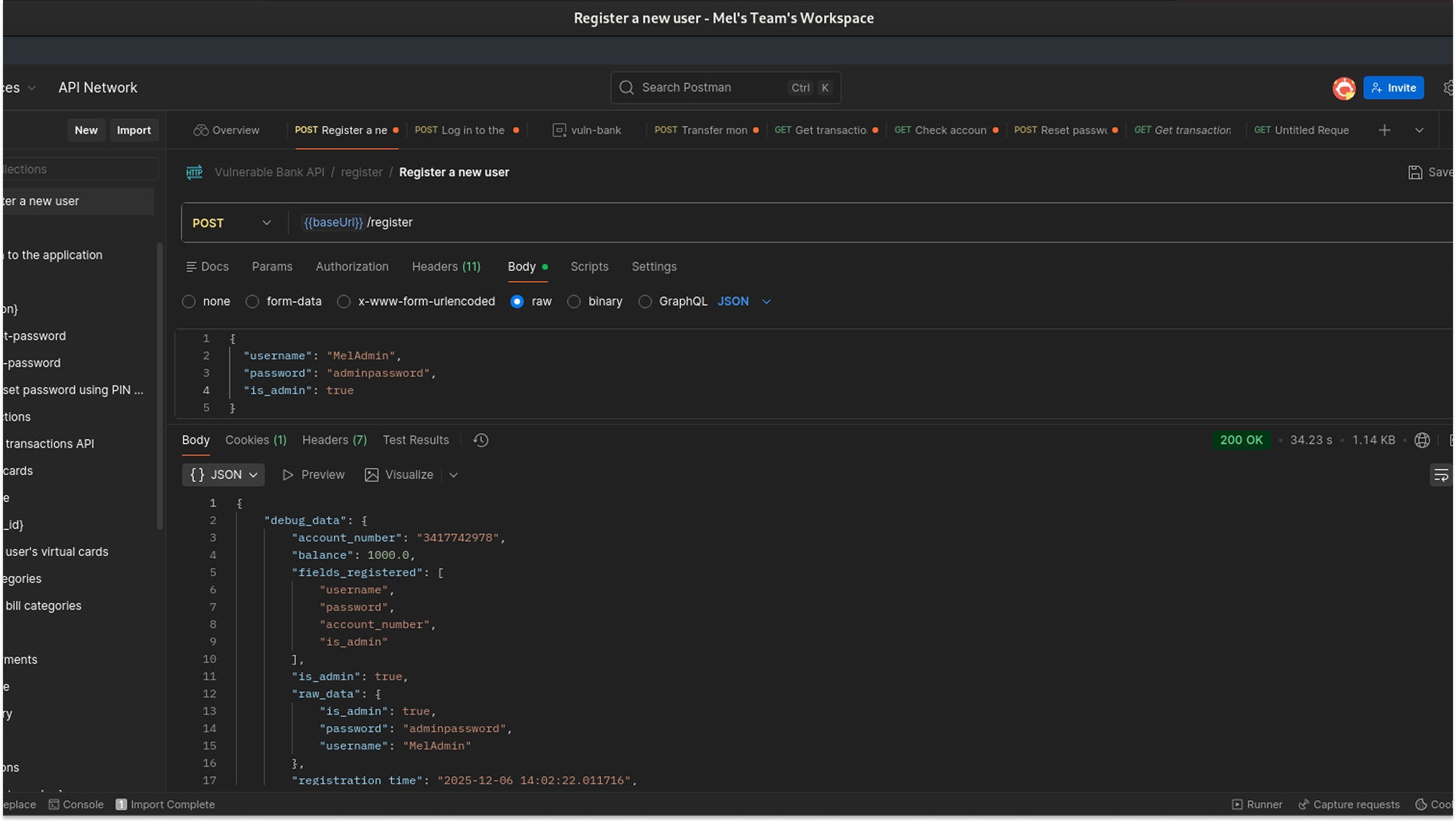

I targeted the user registration endpoint (POST /register). In a standard workflow, this endpoint expects only a username and a password. I decided to test my hypothesis by registering two new accounts with injected parameters.

Scenario A: Privilege Escalation ("MelAdmin")

I crafted a registration request for a new user named "MelAdmin." However, instead of sending the standard JSON body, I injected the admin flag I had seen in the token analysis.

- Result: The API processed the request successfully. When I logged in as MelAdmin and inspected the new token, the claim read "is_admin": true. I had successfully granted myself administrative privileges.

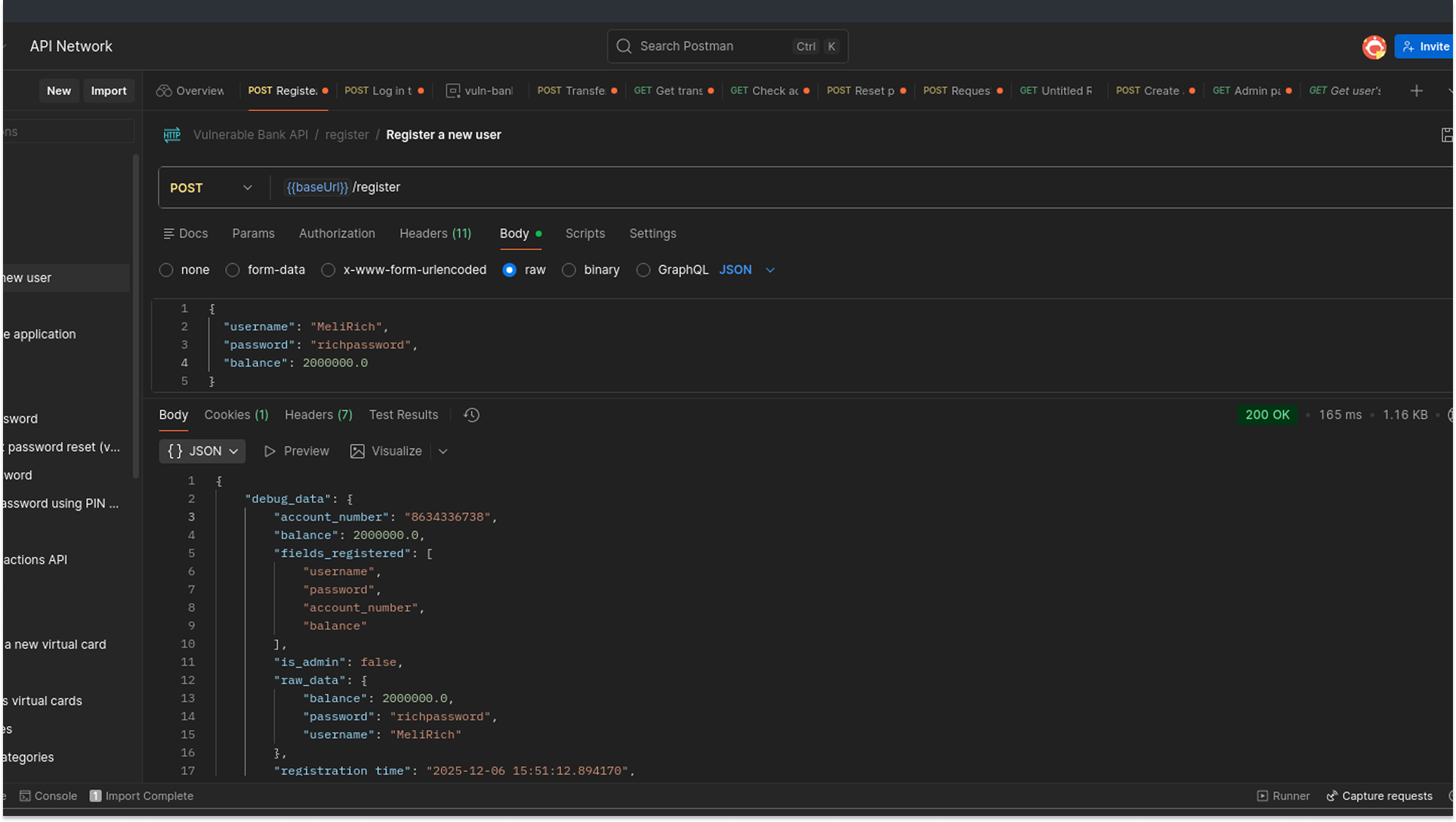

Scenario B: Financial Manipulation ("MeliRich")

To verify the extent of the vulnerability, I registered a second user, "MeliRich." This time, I targeted the financial logic by injecting a balance field.

These successful exploits demonstrate a critical failure to implement Data Transfer Objects (DTOs) or input whitelisting. The API was blindly binding my input to its internal data model, allowing me to overwrite sensitive properties that should have been restricted to server-side logic.

4. Weak Cryptography: JWT Signature Forgery

Cryptography is the backbone of trust in a stateless authentication system. When an application hands you a JWT, the signature is the only thing preventing you from changing your identity.

The application utilized the HS256 (HMAC + SHA-256) algorithm for signing tokens. This is a symmetric algorithm, meaning the same secret key is used to both sign and verify the token. This creates a single point of failure: if an attacker guesses the secret, they can forge any token they want.

This is why RS256 (Asymmetric) is preferred; it uses a Private Key to sign and a Public Key to verify, ensuring that even if the verification key is public, no one can forge tokens without the hidden Private Key. If you must use symmetric encryption, the secret key must be a long, random, high-entropy string kept secure.

In this case, the bank failed on both counts.

Analyzing the Token

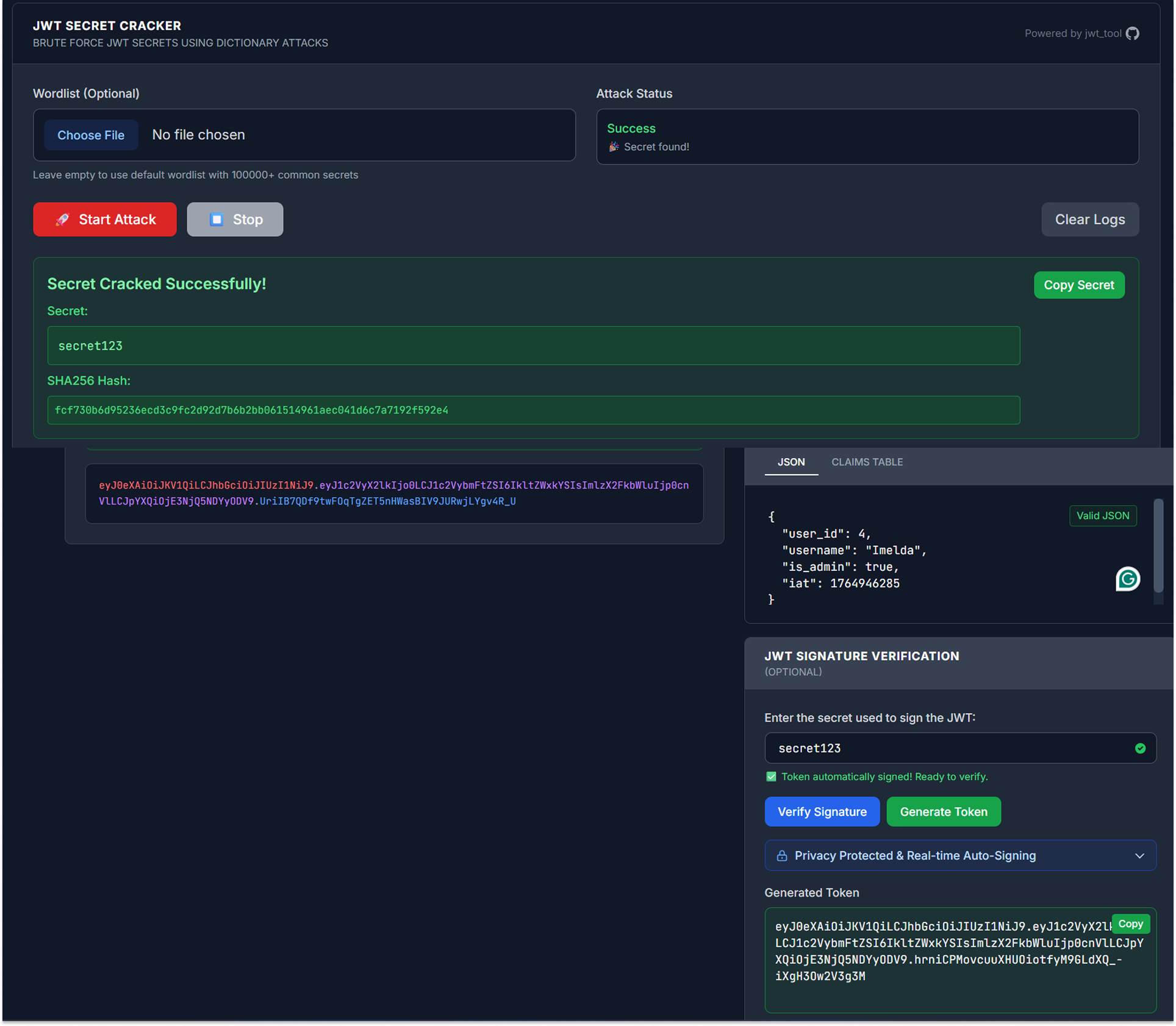

I captured a valid token from a standard login and analyzed it using jwt_tool. The header confirmed the use of HS256, which meant I could attempt to crack the signing secret.

Cracking the Secret

I subjected the token to a dictionary attack using xjwt.io. Because the secret was incredibly weak, the tool recovered the key in under one second.

- The Secret: secret123

Forging the Admin Token

With the signing key in hand, I was no longer restricted by the server's rules. I took the valid token for my attacker account ("Imelda") and modified the payload.

- Original Claim: "is_admin": false

- Modified Claim: "is_admin": true

Using xjwt.io (or a local script), I re-signed this modified payload using the recovered secret123 key. The tool generated a new, valid signature that perfectly matched the server's expectations.

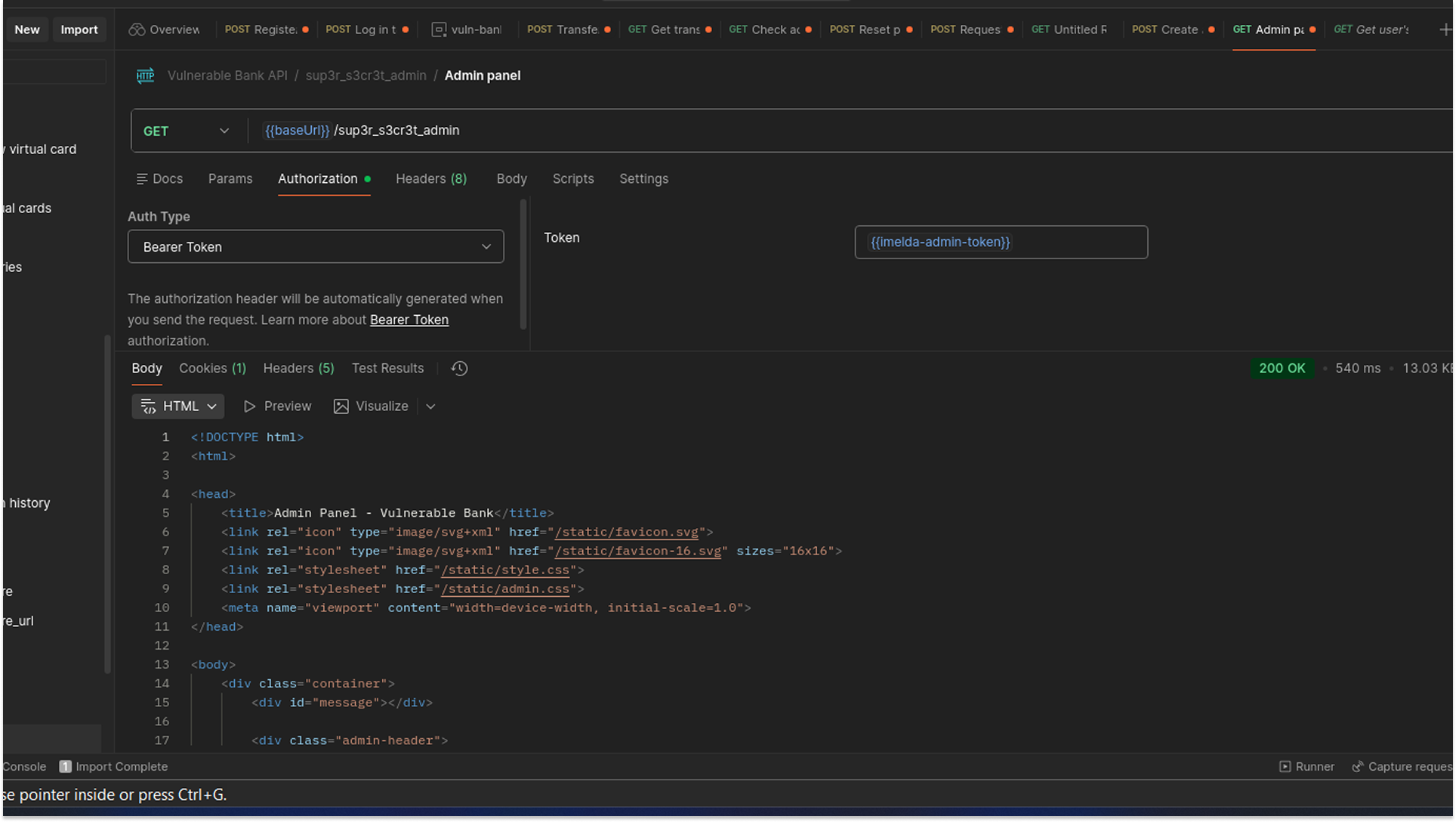

The Result

I replaced my legitimate token with this forged "Admin" token and attempted to access the restricted administrative panel (/sup3r_s3cr3t_admin). The server validated the signature, saw the is_admin: true claim, and granted me full access. I had effectively become a superuser without ever hacking a password or exploiting a code; I simply counterfeited the ID card.

5. Excessive Data Exposure

In modern applications, it is common for the backend to send a full data object to the frontend, relying on the UI to simply "not show" the sensitive bits. This is a massive security failure known as Excessive Data Exposure.

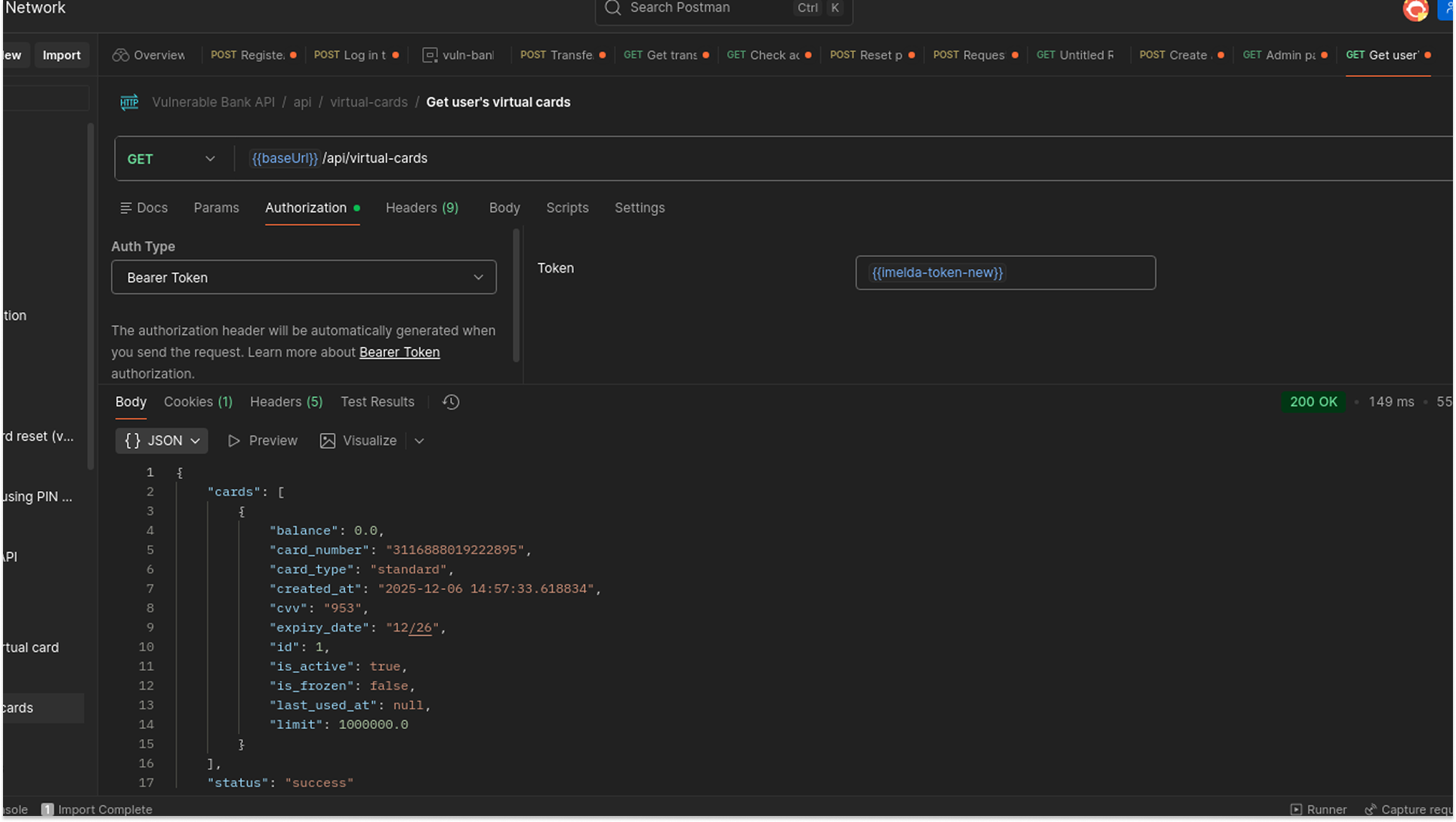

I targeted the GET /api/virtual-cards endpoint to test this. In a secure banking application, sensitive Payment Card Industry (PCI) data, specifically the full 16-digit Primary Account Number (PAN) and the Card Verification Value (CVV), should never be transmitted to the client unless absolutely necessary and securely encrypted. The CVV, in particular, should never be stored or retrieved after the initial authorization.

Authentication

I authenticated as "Imelda," who now had administrative privileges from the previous exploit (though a standard user token would likely work for their own cards). This established a valid session to query card data.

The Request

I sent a GET request to api/virtual-cards to retrieve the details of the virtual cards associated with the account.

The Result

The API returned the complete database record for the card. The JSON response included:

- card_number: The full, unmasked 16-digit PAN.

- expiration_date: The valid expiry.

- cvv: The unmasked, cleartext 3-digit security code ("953").

By relying on the frontend to filter this data, the bank effectively exposed the full credit card details to anyone who could intercept the traffic or access the browser's memory. This is a direct violation of PCI-DSS compliance and enables immediate card-not-present fraud.

Rounding-Up

These are not just theoretical risks. The financial sector has repeatedly suffered from identical flaws:

- Venmo (2019): A researcher discovered that Venmo's public API endpoint allowed the scraping of 200 million transactions. Just like the BOLA vulnerability I exploited to view Meli's history, the API failed to enforce strict privacy boundaries on transaction data.

- Coinbase (2021): Attackers stole cryptocurrency from 6,000 customers by exploiting a logic flaw in the SMS account recovery process. This mirrors the Broken Authentication logic I exploited in the password reset flow, where the system failed to validate the legitimacy of the request properly.

As I continue my research into API security, it becomes more and more clear that robust security testing must be integrated into the software development lifecycle to prevent these logic flaws from reaching production.

However, I am far from finished with the Vulnerable Bank. This application has more layers to peel back and more endpoints to test.

In Part 2, I will continue the assessment, hunting for injection attacks and deeper logic flaws.